Meeting the residents of Merit Place

“There is help out there you just have to reach out,” says one resident of the shelter.

By Macarena Mantilla

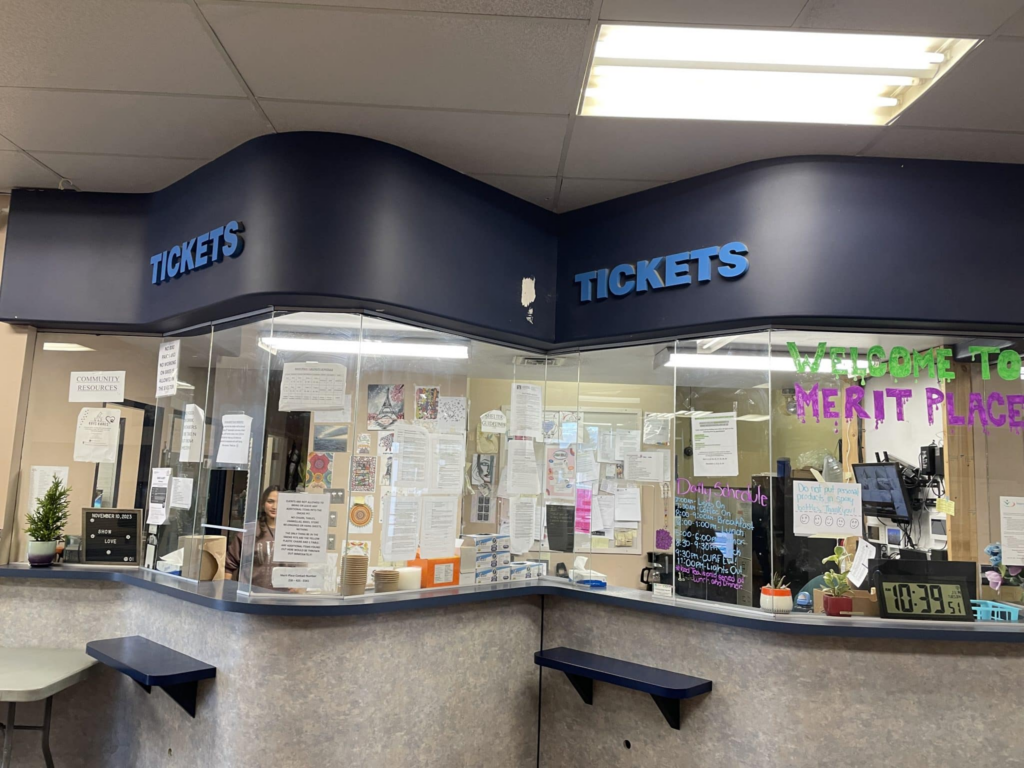

Merit Place is located at the old Greyhound bus depot and serves as the lowest-barrier shelter in Kamloops. Photo by Macarena Mantilla

When I met Dayton Marsh at Merit Place, he came to the office and sat down. He was looking at his hands, wearing a hoodie, a couple of necklaces and a crossbody bag.

He is in his early twenties and is careful to pick his words. After graduating high school he got a job in Rayleigh at a restaurant and then he decided to work in mining for a year. He loved his job at the mine, but started interacting with the wrong group of people.

“I can’t blame anybody but myself,” Marsh says. “Before I knew it I had no job and was homeless.”

After losing his job he lived on the streets for four years, relying on Merit Place for support. He says he would recommend it to anyone seeking help.

“I do not [know] where I would be right now if I wasn’t here,” Marsh tells me. He wants to move into stable housing in the future and seeks to get sober by reducing his use of heroin slowly in order to avoid dangerous withdrawal symptoms.

“There is help out there you just have to reach out,” Marsh says.

Merit Place is located on Notre Dame Drive where the old Greyhound bus depot used to be. It is the lowest-barrier shelter in Kamloops and it is run by the Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA).

“Lowest-barrier” means the emergency housing is made as accessible as possible. If people have been excluded from other shelters for substance use or disruptive or combative behaviour, Merit Place is open for them. In other words, they meet people where they are at.

In Kamloops (Tk’emlúps), like other cities in B.C., the housing crisis that has left at least 312 people homeless is exacerbating frustration from residents who live near emergency shelters like Merit Place.

Since Merit Place opened in February 2022, businesses and neighbours have complained about an increase in theft and graffiti, blaming it on the shelter.

When asked to verify these claims, Kamloops RCMP said they do not compile neighbourhood-specific data related to crime or calls and suggested The Wren file a freedom of information request to learn more.

However, for the 50 people who live there, Merit Place is the only place they can call home while participating in a range of services as they work to find more stable housing.

In addition to providing three meals a day, a place to sleep, showers and laundry, Merit Place case managers attend to each person’s needs and goals, such as completing their Grade 12 education.

In Marsh’s case, staff helped him get his birth certificate.

The shelter also allows pets since some people struggle to find stable pet-friendly housing. They also offer a place to store belongings and help with accessing mail.

Every Wednesday, they host art days where the residents get together and do different activities such as beading, painting and drawing.

On Tuesdays, nurses come into the shelter to treat wounds or other health issues some residents might have.

A look inside Merit Place

When I arrive for a tour of the facility, a worker buzzes me in and the two glass doors slide open.

It was like a ballroom. A ballroom with slow-paced music. Every person is slow dancing by themselves. People go in and out of the dance floor in different directions. Sometimes they are rushed, other times they take their time. All of them are immersed in their technique and their own rhythm.

A booth covered with glass catches the attention of people as they walk in. On top, you can still read the old light blue capitalized letters that spell “Tickets,” a reminder of what the building used to be. The booth is now full of computers, documents, office filing cabinets and the workers of Merit Place.

Behind the improvised offices there is a wall plastered with paintings and drawings. In the lower corner of the wall, was a drawing of a woman, in black pen. Photo by Macarena Mantilla/The Wren

A young man in his early twenties is walking around. His nails are painted black and he has a couple of tattoos on his face and arms. Another man with just one leg is holding himself up with two old crutches while he casually talks to another resident.

The shelter’s 50 units resemble cubicles. Each cubicle has a twin-size bed and a small nightstand. They are divided by wooden walls and the space is very limited, but people have made each their own.

One cubicle is decorated with posters, and a bouquet of coloured flowers stands on the small nightstand accompanied by nail polish. The bed is made and it has some pillows, as if the wooden walls that divided it from others did not exist. Another cubicle has just a comforter, a hamper and some bags on the floor.

At the very end of the room, a door leads to an outdoor patio. As the glass door opens, you can see tin foils dancing on the ground.

No one wants to wind up in a shelter, although it is better than living on the street.

Alfred Achoba is going on four years as the executive director of CMHA. From his experience, most of the people living in shelters are the ones who seek out help because they want to change.

While fear can make some residents hesitant to approach people who are homeless, Achoba says you should treat them like any other person.

“It is like a mirror — what you project is what you are going to get back,” he says. “The necessity is real, the people are real, the people that want to get better are here.”

At Merit Place, housing comes first

A woman enters the shelter with her sunglasses on, holding a pink bag containing a Naloxone kit. The medication Naloxone can reverse and block the effects of other opioids.

While she requests anonymity due to the stigma following homeless people, she tells me she was a server at Red Robin for more than five years. During most of the time she worked there, she struggled with a drug addiction.

She went to the shelter during the first months of 2023 because she had nowhere else to live. The apartment building she was living in changed management and she could not afford the new rent increase, and she became homeless shortly after that. Her addiction affected the possibility of finding another place.

To reach her goal of sobriety, she says she needs to decrease her drug use slowly over a period of time to manage withdrawal symptoms and help her stabilize. Her goal is to reunite with her daughter who lives with her parents.

Her story is an example of many others who end up in a shelter.

The 2023 point-in-time homeless count shows most of the 312 Kamloopsians surveyed wound up homeless most recently due to conflict or abuse from a spouse, friend or family member. The most common barrier to finding housing is affordability, followed by bad credit and a lack of references.

More than a third of people surveyed said they had a medical condition or disability and 65 per cent said they face challenges related to substance use.

Many people who come to Merit Place use drugs, something that Kamloops residents tend to discuss relating to the shelter.

People are allowed to stay at Merit Place even if they use drugs as long as they behave respectfully and do not use them in the booth.

Merit Place has a designated room open to clients of the shelter where they can use injectables safely. The room has windows so workers can monitor the use.

Supervised consumption sites like the one at Merit place contribute to fewer fatal overdoses, reduce public drug use and illness and help connect people to health care services, housing and other supports.

The shelter takes a housing-first approach to homelessness, following direction from the B.C. minister for housing. Research has found that when people have access to basic support like a place to sleep they are better equipped to overcome addiction and other mental health problems.

However, discrimination targeted at people who struggle with substance use remains a barrier. Last year, Kamloops RCMP attended an overdose call at Merit Place where staff overheard Mounties saying it was a waste to use naloxone, Black Press Media reported.

‘I never developed any life skills’

Roughly half of unhoused residents surveyed in Kamloops identified as Indigenous, even though 2016 census data shows they make up 10 per cent of the population.

A third of people surveyed said they were in the foster care system.

Tristan Olson has been living in Merit Place for around a year. Olson lived in foster homes from age six until he turned 18. His experience in foster care affected him deeply.

“I never developed any life skills, how to get a job or how to rent a place,” Olson says.

At 18 years old, he got in trouble with the law.

“I went to adult jail for like a week,” Olson says. “When I got out, they couldn’t put me back in any foster homes.”

Technically an adult at 18 years of age, he explains he was seen as a possible danger to other foster children.

After getting out of jail, his social worker got him into ASK Wellness Society, where he stayed for a while before moving to Prince George. Later on, he came back to Kamloops. When asked if he has ever felt discriminated against, he says he feels it every day.

“They have a reason as to why they discriminate,” Olson says. “That is because homeless people usually steal.”

But that is not a fair assessment of the character of every homeless person, he adds.

He has also struggled with substance use and his goal is to move into stable housing.

A handwritten letter posted on the wall at Merit Place reads: “Thank you very much for helping me feel important, loved and special. I love and appreciate every single one of u in my life as you all played very important roles in showing me purpose and ways to function accordingly in public to stay well.” Photo by Macarena Mantilla

Community compassion could help

Jennifer Healey is the manager of shelter, assessment and triage at Merit Place. The goal of emergency shelters is to find homeless people stable housing. Healey’s job is to determine where and when.

Some people outgrow the program at Merit Place then move into Emerald Centre, which is an emergency shelter with supports. Moira House has a supportive housing program and is the next step after they see more improvement from clients.

Moira House’s supportive housing is a communal living building with staff available 24 hours a day. They provide meals and wellness checks. There they support clients with basic life skills, finding employment and connecting them with other supports.

Healey says most of the clients feel ashamed and looked down upon when they try to reintegrate themselves back into society. If they are sick, they avoid going to the hospital because they would rather avoid the comments or looks from others.

“We do get a lot of people unfortunately that have been to treatment and then they are discharged from treatment with nowhere to go,” Healey says.

The shelter takes them in and evaluates the best way they can help them. Some people have mental health problems but have no support or are undiagnosed. They work with different individuals with different needs, levels of addiction and mental health problems.

Healey says she gets constant calls from community members.

“I received a message saying that someone graffitied all over the street and the assumption was that it was a client here,” Healey recalls.

The person accused of doing the graffiti is not someone who has used the shelter.

There are guidelines in place that the clients have to follow in order to stay at Merit Place, Alfred explains. Residents have to sign a good neighbour agreement, a document which stipulates they will follow the rules, be respectful to neighbours and report any hostile behaviour.

Residents cannot bring any stolen items to the shelter as a part of the guidelines. CMHA also conducts random bag searches and clean-ups to ensure everyone’s safety. If a client violates the agreement they will be asked to leave the shelter.

The shelter encourages clients to clean up after themselves and provide a friendly environment to everyone. Photo by CMHA

Healey says she also hears rumours that people only stay at the shelter to use drugs. However, she has made it clear they require residents to be respectful and work toward developing life skills.

“There is always a ‘why’ there to somebody’s current story,” Healey says. “People just don’t choose to be here.”

Most homeless people have complex trauma, she explains, a mental health condition that can cause flashbacks, anxiety, insomnia, isolation and other behaviour changes.

“As a community, people could help by educating themselves a little bit more so they have their understanding,” Healey says.

One of the main problems she has seen in the community is that most people are uneducated on the subject of homelessness.

Healey says that she is always open to having conversations with members of the community who are curious about learning more about Merit Place.

Residents can reach out to the CMHA to find ways they can support with donations or to get involved in other programs.

For the full article published at the Wren click the link below

Meeting the residents of Merit Place